Half of High-Rise Mortgage Valuations Still Require an EWS1 Despite Industry Pledge

In an attempt to revive the flatlining market for flats affected by cladding and other building safety defects, major mortgage lenders pledged in December 2022 that they would lend without an EWS1 form being required under certain conditions. However, the latest government data shows no improvement on this measure since reporting began three years ago.

In a significant number of cases, it appears that lenders are continuing to request an EWS1 form if there are concerns that leaseholders or potential buyers could face costs to fix fire safety defects; a rating of “B1” or above would be needed to indicate that a building will not need expensive remediation work.

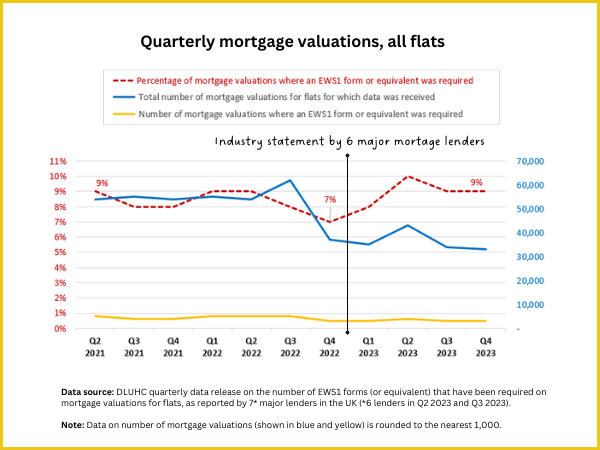

DLUHC data from 6-7 major lenders shows that in October to December 2023, an EWS1 was requested for 9% of all flat mortgage valuations – exactly the same as the proportion requested in April to June 2021, the earliest period for which data is available. An EWS1 (or equivalent) was requested for at least 13,000 mortgage valuations in 2023, which are likely to relate to thousands of different buildings.

A pledge to revive the flatlining market

In December 2022, an “industry statement,” supported by UK Finance, the Building Societies Association and RICS, had promised that the “big six” mortgage lenders would consider lending on affected flats without requesting an EWS1 form. Instead, leaseholders would only need proof that remediation works would be funded by a recognised scheme (either remediated by a developer or government funding) or that a qualifying leaseholder would be “protected” by a cap on costs, as evidenced by a Leaseholder Deed of Certificate. By December 2023, nine lenders had signed up to the commitment to lend without an EWS1 and they represented more than 75% of the mortgage market, according to data from UK Finance.

This sounded positive and should have been an additional escape route for hundreds of thousands of leaseholders who had been unable to remortgage, sell or move on with their lives since Grenfell.

Whilst giving evidence to the Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee in March 2023, Housing Minister Lee Rowley spoke candidly about the state of the market at the time the lender pledge was made. He said, “until a few months ago, I think it is fair to say that there wasn’t much activity at all in the market.” The Minister’s hand gestures communicated more clearly than his words how dead the market was considered to be.

If the Government’s rhetoric that “the market has opened up” is accurate and if the industry commitment was working in practice, we would have expected to see a noticeable and sustained reduction in the proportion of mortgage transactions where EWS1 forms were requested. However, the statistics do not show any discernible improvement. As our graph shows, the position appears to have got slightly worse, not better, since the end of 2022. At that time, only 7% of flat mortgage valuations had required an EWS1.

No reduction in EWS1 requests for mid-rise or low-rise flats

For high rise flats, around half of mortgage valuations still require an EWS1. The data does suggest there may have been a slight downward trend, decreasing from 52% in April to June 2021 to 46% in October to December 2023. But this figure is still extremely high and the pattern remains unpredictable; for example, in April to June 2023, as many as 62% of high rise mortgage valuations required an EWS1.

Most buildings that have completed cladding remediation to date or which have clear remediation plans in place will be high-rise, on the basis that these are usually prioritised for works, having usually been deemed to be higher risk. Therefore it must be perplexing to the Government that so many high rise properties still don’t meet the criteria to satisfy lenders without an EWS1 being requested.

For mid rise flats, an EWS1 is still requested for a quarter of mortgage valuations (25%). This has barely budged since Q2 2022 (the earliest period with comparable data), despite new remediation funding schemes for mid rise buildings coming onstream since then. By the end of December 2023, 88 mid rise buildings were confirmed as eligible for government funding under the Cladding Safety Scheme and 544 were marked for remediation under the developer contract. However, these funding “solutions” appear to have had no effect on the proportion of mid rise mortgage valuations that still require an EWS1.

The proportion of low rise flats (1-4 storeys) requiring an EWS1 has also stayed relatively static over time, at 2% of mortgage valuations. This figure may seem low, but it is worth bearing in mind that this data could include flats in converted houses, not just purpose-built blocks. Low rise mortgage valuations are also far more numerous than other height categories – which means that there is a surprisingly large volume of EWS1 requests for buildings of this height. Despite DLUHC frequently downplaying the impact of the building safety scandal on leaseholders in low rise buildings, calculations using the Department’s data show that as many as 1 in 6 of all EWS1 requests are for low rise buildings (1-4 storeys).

Based on limited data from 4-5 mortgage lenders (and therefore this should be considered an underestimate), an EWS1 was required for mortgage valuations on around 2,000 low rise flats in 2023 – which could be scattered across 2,000 different buildings across the country.

It is absurd that leaseholders in buildings under 11 metres are ruled “out of scope” for protection from remediation costs but may still be asked for an EWS1 form if they want to remortgage or sell. Leaseholders in buildings of this height often struggle to get their building owner to commission an EWS1 assessment, or the building will be low priority and “at the back of the queue,” which could take years. And with no protection from relevant costs under the Building Safety Act, they will also have to pay for any fire safety related surveys including an EWS1 assessment. It’s clear from the data that the situation is not as problem-free for leaseholders in buildings under 11 metres as the Government would like to think.

The lender commitment is still not working in practice

So why are we not seeing any reduction in the requirement for EWS1 forms, despite the lender pledge?

The reality on the ground remains very inconsistent and lenders retain their right to make commercial decisions on a case by case basis. We continue to hear from large numbers of leaseholders that even where they meet the criteria laid out in the industry statement, a lender will often ask for additional information such as remediation start and end dates or a confirmed scope of works – which were not a condition of the industry pledge. This is information that a majority of buildings still do not have. As a result, even leaseholders who have confirmed funding for remediation works and/or qualify for the Government’s leaseholder protections may find they cannot remortgage or sell to a buyer who requires a mortgage.

We have lost count of how many developers have casually informed us that leaseholders are no longer trapped because they have provided a “comfort letter” confirming that remediation is covered by the self-remediation contract. We do hear some success stories, where this has sometimes been sufficient to remortgage or sell a property, without resorting to a distressed cash sale. But developers seem to either be not aware or not acknowledging that the continued delays in providing remediation start and end dates and a detailed scope of work – and ultimately fixing buildings at the quickest pace possible – are still blockers for many leaseholders who want to move on with their lives.

Developers have also pointed out to us that the self-remediation terms created no obligation on them to commission an EWS1 – perhaps because the government assumed the lender pledge would be working in practice. This leaves some leaseholders trapped even when their building is lucky enough to be in scope of the developer contract. If the building previously “failed” an EWS1 assessment (with a “B2” rating) but the developer now declares remediation is not necessary and they will not commission a new EWS1 to supercede the old one, a mortgage may be declined as soon as the lender chooses to ask for the building’s EWS1 – which the statistics show is still a very common request.

Too few leaseholders have a funding solution for all building safety defects

The elephant in the room is that fewer buildings than the Government wants to admit have an assured funding solution to cover the remediation of all defects, which will satisfy lenders and future buyers.

There is still no funding solution for non-cladding defects, unless the building happens to be in the cohort of around 15% of an estimated 10,000 unsafe buildings that are covered by the developer contract, or the building’s freeholder meets the developer test or contribution condition and they will therefore fund remediation without passing costs on to leaseholders (only protecting qualifying leaseholders in the latter case). DLUHC has so far chosen not to collect or publish data on buildings where remediation will be funded by freeholders, so there is no evidence regarding the number of buildings that might have this pathway to remediation funding.

Where a developer or freeholder is not funding the remediation of non-cladding defects, even qualifying leaseholders could face capped costs of up to £15,000 in London or £10,000 outside London (more for higher-value properties). This is not an insubstantial charge and could represent up to 5% of the property value. Because the Government failed to give full cost protection to leaseholders, a valuer might therefore still request an EWS1 in order to quantify the risk and assess the impact on property value.

Some leaseholders are excluded from the lender commitment

The lender commitment also excludes non-qualifying leases, held by buy-to-let landlords who own or co-own more than three UK properties; buildings under 11 metres, where leaseholders are liable for both cladding and non-cladding costs; and enfranchised or leaseholder-owned buildings, which are not covered by the Building Safety Act’s “leaseholder protections” and cannot evidence a cap on non-cladding costs.

RICS guidance specifically highlights that there may be no pathway for non-qualifying leaseholders to remortgage their properties, in scenario 4.2.4 of the Valuation approach for properties in multi-storey, multi-occupancy residential buildings with cladding, which says: “For remortgages, mainstream lenders may choose not to lend… Mortgage finance may not be readily available from mainstream residential mortgage lenders, particularly if the non-qualifying leaseholder client is seeking remortgage.”

For buildings under 11 metres, even if there are no known defects, it may still be difficult to secure a mortgage without an EWS1 to prove it. Although only a small proportion of buildings of this height may require expensive remediation, the lack of any funding scheme and the lack of a cap on costs has a ripple effect on all buildings of this height, and it can result in excessive caution by some mortgage lenders.

Transparency about the impact on sales activity and property values

The Housing Minister appears to think the mortgage lenders’ commitment is working. In a recent Building Safety statement in parliament, he said: “Since December 2022… the mortgage sector has been freed up to allow people to take mortgages, to remortgage and to move properties when big life events happen, and we hope that that will continue. I am monitoring, on a month-by-month basis, the large banks and building societies that are providing mortgages, and I can see that progress is being made.”

But the experience of leaseholders on the ground and EWS1 data – the only dataset the Government has chosen to publish in relation to the market for affected flats – suggest that progress still remains limited, at best. If the Government has alterative data demonstrating progress, then leaseholders would welcome this; many remain reluctant to try to sell without evidence that the market is substantially opening up, because they cannot risk incurring costs on what appears to be an inconsistent game of luck.

There continues to be a high level of uncertainty and misunderstanding amongst estate agents which may be another factor discouraging people from trying to sell properties before remediation is complete; leaseholders regularly report that an estate agent has advised that they will only be able to sell to a cash buyer without an EWS1.

Some leaseholders, particularly non-qualifying leaseholders, may also find it harder to find a conveyancer that will act on the sale of their lease, due to the complexity of the leaseholder protections. For example, buyers’ solicitors cannot check how many properties the seller or previous seller held as at 14 February 2022, so they cannot verify sellers’ claims that leases qualify for leasehold protection – and as a result some are choosing to limit their risk by reducing the scope of what they can advise on or ceasing to act on leasehold flat transactions entirely.

We have repeatedly asked the Government to work with mortgage lenders to collect and share further data on both transaction volumes and average transaction values compared to pre-Grenfell times. Other general market factors – including the pandemic and the rapid escalation in mortgage interest rates in 2022 and 2023 – will have undoubtedly affected the ability to sell or remortgage all types of property in recent times. However, analysis that compares buildings affected by cladding and building safety defects against a control group of unaffected buildings should not be beyond the means of our banking sector.

Leaseholders who needed to sell their home since June 2017 – and were lucky enough to be able to do so – have sometimes had to swallow substantial financial losses, particularly if they sold to cash buyers. “Relevant” building safety costs are capped for qualifying leaseholders under the Building Safety Act, and in a just world this would include any impairment to property values suffered as a result of the building safety scandal. We will be continuing to push DLUHC for more transparency on this.

Call to action!

If you are having issues with mortgage lending that you want to escalate to DLUHC, you can contact [email protected] Please include your full address and postcode, the height of your building or number of storeys (if known and relevant), an overview of the issues you are facing (please attach any relevant documentation), and any reference numbers that you have from previous correspondence with the Department. Please specify the mortgage lender involved and include mortgage reference numbers if known.

Please copy our team at [email protected] so that we are aware of issues being raised and can follow up where necessary. We have been advised that responses should be provided within 20 working days, so please send a chaser email to DLUHC if you do not receive a reply within that time frame.

The End Our Cladding Scandal campaign calls on the Government to lead an urgent, national effort to fix the building safety crisis.

Follow us on Twitter

for important updates on the campaign, ways to get involved and new information

The post Half of High-Rise Mortgage Valuations Still Require an EWS1 Despite Industry Pledge appeared first on End Our Cladding Scandal.